On Tuesday evening, The Wall Street Journal published a high-level overview of a report produced by Chess.com, all about Hans Niemann, the player suspected of cheating at the Sinquefield Cup against reigning five-time World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen. (Possibly, the internet has repeatedly joked, with the help of anal beads.) Not only did the chess website defend its decision to ban Niemann from online play, it also made the shocking allegation that it had concluded the young grandmaster had cheated in over 100 online games. Now the full report is out, and it’s a whopping 72 pages full of graphs, appendixes, and exhibits of evidence that more or less say the same thing, but in further detail. The report also heavily features other cheating cases beyond the ones making the headlines, but we’ll get to that in a moment.

I’m sure that many will be debating whether or not it’s fair to punish Niemann without proof he ever cheated in a real-world setting, and why Chess.com thought it fit to let Niemann initially continue playing on its website if, in fact, there exist dozens of pages of information that suggest he is a perpetual and habitual cheater. The evidence is at once overwhelming, and has been for years, yet Chess.com insists that its system is world-class in finding cheaters, to the degree that many who come under the site’s scrutiny end up confessing their misdeeds. Chess.com clearly discovered Niemann was a cheat, of course, but didn’t think his history was a danger until it became a huge controversy. Niemann was temporarily banned from the website in 2020, but went on to play in real-world settings alongside online tournaments that awarded prize money not long after. Somehow it took until now for events to really take a turn, as Niemann has been re-banned from the website and also barred from playing in a Chess.com championship, with a prize pool of $1M, that he had previously been invited to.

The website’s report literally says, emphasis ours, “...we had suspicions about Hans’ play against Magnus at the Sinquefield Cup, which were intensified by the public fallout from the event,” meaning that the public perception did play a part in the timing of this all. And the document’s introduction has Chess.com positioning itself as a steward of the game itself, with a responsibility to grow the game’s fanbase and keep things fair. With $1M on the line in Chess.com’s Global Championship, it argued, it simply couldn’t ignore the explosion that was underway.

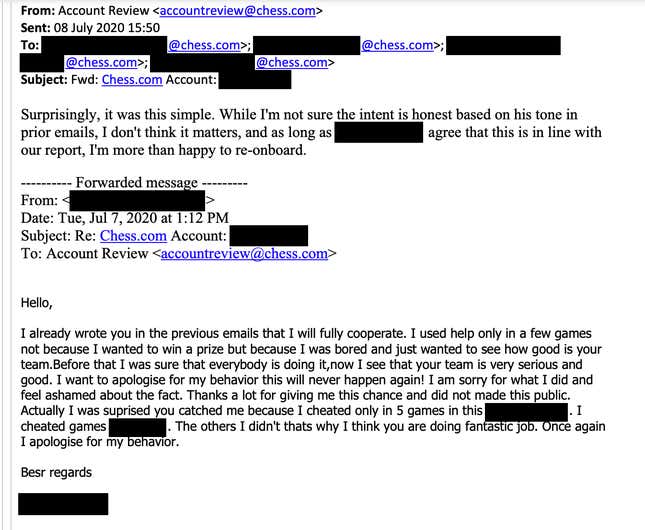

To the site’s credit, the document’s introduction also admits that the organization probably could have made better decisions about this situation; it is, after all, run by humans. But if you’re confused as to how or why events unfolded the way they did, I bring your attention to the report’s “Exhibit C.” It contains a series of emails which Chess.com cites as an example of an interaction it had with another top player who apparently cheated, and I think it’s pretty illustrative of how the website operates overall.

“This person competed in a single event featuring 10 total games in 2020. Their Strength Score alone was not necessarily enough to act, but indicated that there was the potential for cheating,” the report reads, in reference to the scoring system the website uses to catch fishy business. “Even considering this player’s Elo rating of nearly 2700, our expert team was able to discern the truth that this player was indeed selectively cheating using a chess engine. When confronted with our allegations that they had used outside help, they confessed, as shown in the redacted email exchange attached as Exhibit C to this report. This email chain reflects the deliberateness of our process and how we engage with players like Hans, who are suspected of cheating on the platform.”

Read More: Chess Champion Breaks Silence On ‘Anal Bead’ Cheating Controversy

While the player initially plays dumb, eventually it becomes evident that they’ve been caught red-handed. But here’s where it gets really interesting, as rather than simply banning the cheater outright, Chess.com gives him a chance to come clean:

As a titled player, we would like to offer you a chance to reestablish yourself within the Chess.com community, and because of that, we have made no public statements regarding the reasons for your account closure or our findings. If you choose to acknowledge any of the behaviors that you feel might have resulted in your account being closed within the next 72 hours, we may try to work with you privately to have a new account opened, equipped with a title and Diamond Membership.

And here’s the player, complying (grammatical errors theirs):

Hello, I already wrote you in the previous emails that I will fully cooperate. I used help only in a few games not because I wanted to win a prize but because I was bored and just wanted to see how good is your team. Before that I was sure that everybody is doing it, now I see that your team is very serious and good. I want to apologise for my behavior this will never happen again! I am sorry for what I did and feel ashamed about the fact. Thanks a lot for giving me this chance and did not made this public. Actually I was surprised you catched me because I cheated only in 5 games in this. I cheated games. The others I didn’t thats why I think you are doing fantastic job. Once again I apologise for my behavior.

Sure, this entire thing is mostly here for Chess.com to boast about its cheat detection: Not only has it caught plenty of players before, some of those players were top tier! You should trust its methodology when it says that Niemann has cheated profusely, is its whole spiel. Even the cheater gives the detection team props for how good they are. But what I want you to take away from this is that there was a big element of trust placed with the cheater, provided they were willing to own up to what they did. Consequences were suffered, but they still let the player continue using the site under the assumption that, as promised, they would never transgress again. It didn’t matter that they were a top 100 player, they still got a chance to redeem themselves.

Which now brings us to Niemann. The site says Exhibit C is a showcase of how it approaches situations like that of Niemann, and presumably something very similar happened back in 2020, when he was originally caught. Chess.com says in the report that, even more recently, “It has historically been Chess.com’s general policy to handle account suspensions/closures and invitations for titled players (such as Hans) in a non-public manner.” Clearly it trusted him to come back and play and hoped he would keep it clean, because the original ban only lasted six months. Perhaps it’s not so much that this is coincidental timing, as much as it is that the people who see themselves as the stewards of chess have always wanted to create a healthy community where it’s possible to rehabilitate. Niemann may have been a cheat, but they wanted to give him an opportunity to be a better player.

It might seem like pulling this now is a breach on Chess.com’s part, but remember, in light of the accusations, Niemann assured the public he had only cheated a couple of times, and that these instances happened a good while ago, when he was younger. If Niemann was lying about that, and doing so very recently, you could make the argument that he broke the pact here first and therefore couldn’t be trusted to further Chess.com’s larger aim to keep the game honest.

Of course, plenty of observers will still have their doubts, especially when you consider that the website has made an offer to purchase Magnus Carlsen’s company for millions of dollars. The report repeatedly tries to assure the reader it isn’t favoring Carlsen in any way, with one of the first big sections dedicated to whether or not its decisions were influenced by the grandmaster. Nevermind that we still don’t have evidence that Niemann ever cheated in an over-the-board setting, with theoretical anal beads or not.

Still, I encourage you to spend some time reading Chess.com’s enormous 72-page report: Whatever you take away from it, it’s a fascinating and unprecedented look inside one of the year’s biggest competitive scandals.